This story must necessarily begin with the route of Richter’s Promenade.

Hugo Richter’s historic route was roughly 5 kilometres long. The route ran along the former Freight Rail Ring Road of Wrocław at today’s Krzyki.

The route began at an overpass in ul Grabiszyńska, near plac Srebrny. Then it turned to the south and continued along the inner side of the railway embankment to cross today’s al Hallera and ul Racławicka, where it crossed an overpass to reach an outer side of the embankment.

One could later climb a hill called Mała Sobótka or continue their journey to the south, reaching al Karkonoska and the Centennial Stone. One could also follow underneath a nearby underpass to reach Południowy Park. And follow later to Górka Partynicka. The route came to an and at an overpass in ul Borowska, near the University Research Hospital. The route reached its destination at Wojszyce.

Was it a hard-surface avenue for strollers?

The route varied at particular sections. It was between one to three metres in width. And it sometimes turned into a narrow pathway. For example, today’s terminus at Krzyki, was a dirt road planted along with rows of trees. More emphasis was laid on greenery and landscape design than the road itself.

Was the vegetation around unique or original?

The tree species were selected suitably to their setting and included the Norway maple, common oak, little-leaf linden or chestnut trees. Some of the sections featured the northern red oak, mainly on the inner side of the embankment. In my thesis I argue this was because of the double function of the embankment, which served not only railway transport purposes, but was also designed as an element in the 19th-century fortification system. Defences such as these were usually covered by tactical greenery to screen them against the enemy’s reconnaissance. The trees and shrubbery were intended to screen the embankment.

In the late 19th century, Krzyki was mainly covered by fields with sparse farming colonies. The city began in today’s ul Wielicka. Hence the idea to build a strolling promenade just outside of the city?

This calls for a digression into history and great politics. The latter part of the 19th century saw the unification of Germany and the rise of the Central Powers and Ententa. The Second Reich was faced with the prospect of double invasion from France and the Russian Empire. One of the ways to address the issue was the Supreme Federal Directive from 1889, which envisioned Wrocław as one of the seventeen cities to be developed into strongholds.

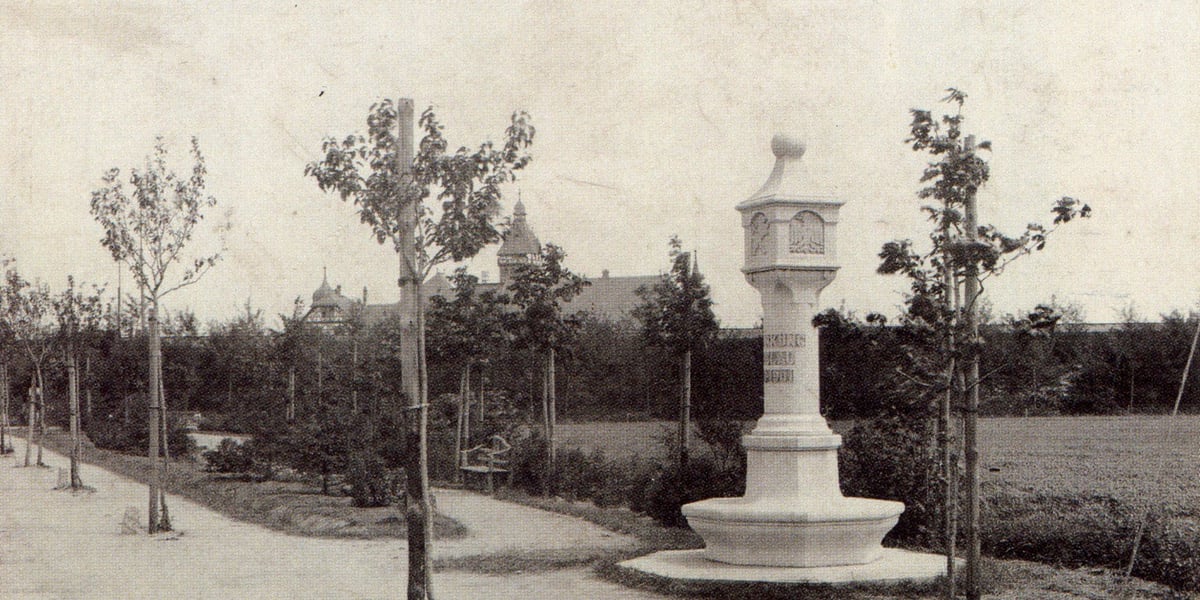

Hugo Richter’s Promenade, photograph Eduard van Delden, early 20th century.

The construction of the fortifications around the city began the following year. A massive embankment designed as an artillery fortification and major railway route was developed in the fields in the southern outskirts of the city. The earth remaining after the construction process was used to develop several randomly located hills: today’s Mała Sobótka, Wzgórze Bendera in Południowy Park and Górka Partynicka. This major interference with the landscape led to its significant degradation. A decision was made to alleviate the negative impact of the embankment on its surroundings.

What about Richter’s Promenade itself?

The facility was created on the initiative from the Association for the Beautification of the City of Breslau, which was chaired by Breslau’s Mayor Georg Bender. The association was an auxiliary organisation that supported the city for greenery and aesthetics. The Association gathered Breslau’s elite, including entrepreneurs, politicians, the military and architects, including the promenade’s designer Gardening Inspector Hugo Richter and Construction Counsellor Richard Plüddemann. The association’s reports suggest that the former was responsible for greenery while the latter contributed an architectural design in collaboration with Carl Klimm.

The major section of the promenade spanned al Hallera and ul Powstańców Śląskich. The section served as a strolling link between Południowy and Grabiszyński Parks. The parks and the promenade were developed as a green ring surrounding the city centre. Hugo Richter’s promenade served as the backbone of the system.

Have any other parts of the system survived?

A strolling route along the Oder levees was developed in the north. The route connected the Wrocław Zoo and Szczytnicki Park with Osobowicki Forest. Beautifully restored oaktree promenades have survived along ul Pasterska.

The east side of the city featured a short route leading through Rakowiecki Forest between ul Wilcza and ul Na Grobli. All of these routes have survived, but they are no longer easily recognised these days. Before World War II, the surrounding areas developed with new garden estates, vantage points, sports fields and allotment gardens, which are still in use today.

What leisure facilities were featured along Richter’s Promenade?

The facilities were quite diverse. Vantage points were the promenade’s main attraction. In late 1930s, there were four such points along the route: Hardenberg’s Mound (today's Gajowickie Hill), Mała Sobótka, Bender’s Hill in Południowy Park and Riemann’s Hill (today's Partynicka Hill) in ul Koszyckiej, which is now a little and overgrown precipice. The hills commanded a beautiful view of the southern outskirts of Breslau and the mountains.

Hugo Richter, source: Bińkowska I. 2006. Nature and the city Public green area in Breslau from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries.

The promenade ran along sports fields. Take the recently developed Ogrody Hallera estate, for example. The area was occupied by the Silesian Sports Club, which transformed into PaFaWag after World War II.

Along the route, Schreber’s gardens extended, together with several sports fields, leisure areas and playgrounds. Commemorative stones were laid and symbolic memorials were erected, including the Centennial Stone in aleja Karkonoska. Today’s Ołtaszyn was known as Bismarck Platz, and it featured two sports fields. Today’s allotment gardens in ul Koszycka were formerly known as Körner’s Fields, which served as a leisure area.

There was also some entertainment on the way. Restaurants, brasseries and taverns were developed along the promenade. Hasse’s Restaurant in Południowy Park was the most popular of them all. However, there more places to enjoy beer and music in the area.

Did the residents of Breslau like the promenade.

They did a lot. At the beginning of the 20th century, a Breslau-based writer called Hugo Kretschmer reminisced about thousands of people strolling along the promenade. For the community, a walk along the promenade was like a day trip out of the city. There was a tram terminus in ul Grabiszyńska, and one more in Południowy Park. With public transport, local residents enjoyed easy access to the promenade.

The area catered to the idea of regional tourism, which developed rapidly at the time. “Strollers used to explore the outskirts of the city, seeking intriguing spots, historic sites or scenic vistas. Some people just couldn’t afford to travel further away from the city. The promenade catered to their needs with a necessary minimum such as hard-surfaced pathways and vantage points.

The hills I’ve already mentioned commanded a beautiful view of the mountains. The strollers could admire Ślęża Massif, the Giant Mountains, the Owl Mountains and the Jeseníky Mountains in the Czech Republic, which are located 140 km away from the city! A hill called Górka Skarbowców even featured a gazebo and a board with a description of the mountain panorama. The vantage points were considered a great attraction in the local community. One interesting thing is that a section of Południowy Park that was adjacent to the embankment was planted with alpine greenery, the architecture in the area resembling that of Switzerland. The entire Hugo Richter’s promenade commended the mountains of Lower Silesia, as it were.

How long did it take to build the promenade?

Large facilities such as this do not spring up just like that. The promenade evolved for nearly half a century. The development was completed in two distinct stages. From the late 19th century, when the development of Południowy Park began, until World War I, Richter can be said to have had a real impact on the promenade. The 1920s and 1930s brought a “modernist” stage, which saw the development of modern sports facilities and large housing estates in Grabiszyn, Borek and Krzyki. Hugo Richter was retired at the time, while the Association for the Beautification of the City of Breslau suspended activity after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

A vantage point on a hill in Południowy Park, early 20th century, source: http://dolny-slask.org.pl/

Despite all this, Richter’s idea was organically continued by the Wrocław Municipal Office and private investors who sought to redevelop the area as a truly urban environment.

Which parts of the promenade have managed to survive?

I have to admit that different sections of the promenade have survived to a varying degree. Some of them are virtually non-existent while some others are only slightly neglected.

First off, the promenade lost continuity when it was dissected with several heavily congested roads. Vantage points were covered with self-seeders, Gajowickie Hill being the only one to offer a vista of the mountains. The dendrochronological inventory demonstrated that only short intermittent sections of the originally planted trees have survived. With the exception of the Centennial Stone, all German memorials were destroyed. The same happened to garden furniture. Only one pavilion in Bender's Hill have survived.

Despite all the changes for the worse, the promenade still has a lot to offer to the strollers. We have beautifully restored squares, including Lipowy, Dębowy and Bismarcka, which are lined with old trees. Some of these are monument-sized specimens, around 50 of them scattered along the promenade, Admittedly, the promenade of today is nothing like the promenade in its former glory. However, the remains allow a gradual regeneration process.

Are the surviving sections of the promenade used for strolling these days?

Yes, they are. I’ve met dozens of strollers along the promenade at sunny weekends. The promenade is also very attractive to runners and cyclists. The local residents use the promenade as a daily short cut on their way to work, as it provides a convenient link to several housing estates Sadly, nobody knows they are using a historic pathway.

What can be done to improve the functional aspect of the promenade without too much spending?

First of all, we must provide access and convenient connections to particular sections of the route. Strollers have no difficulty in crossing some of the minor streets in the area. They simply take a zebra crossing. The most challenging section is located near al Hallera, which strollers have to bypass because of major denivelation. There is a footbridge nearby, but no access to cyclists have been provided.

Historic alleyways should be renovated and replanted at the same time. Special care should be given to some of the most valuable tree specimens, which do rather badly in urban conditions. Many locations, especially at Grabiszyn, need new rows of trees to be planted for the strollers not to promenade among the garages.

A view of Riemann’s Hill towards the South- East, photograph Eduard van Delden, early 1970s.

It is also important that basic facilities for cyclists and pedestrians are provided: hard-surfaced roads, benches, bins and lighting. Hills should also be restored as vantage points. This, however, would called for some proper logging, which might in turn incite protest in the local community. The strollers would certainly welcome the idea to open the adjacent allotment gardens or provide access to Racławicki Pond.

That said, all these postulations are not feasible at all. A team of urban planners at the Wrocław City Office have been working under Monika Kozłowska-Święconek to develop a regeneration project for the route as a prospective Krzyki Promenade. The plans provide for a cycling route and illumination along the existing section of the promenade between Południowy Park and Mała Sobótka, so perhaps Hugo Richter’s Promenade will regain its former glory one day.

*

Jacek Kuśmierski is a Landscape Design graduate from the University of Life Sciences in Wrocław. His Master’s thesis „Promenada Hugo Richtera jako element systemu ścieżek spacerowych Wrocławia” [Hugo Richter>>'<

Jacek Kuśmierski works at the Garden Section of the Wilanów Palace Museum in Warsaw.